‘Ulu Deficiency Symptoms in Hawai‘i

We often get asked, “What’s wrong with my ʻulu?” So we’ve teamed up with Kahealani Acosta and Dr. Noa Lincoln of UH Mānoa to create a list of common nutrient deficiencies and their symptoms to help growers quickly identify problems and get on track to addressing them.

Because healthy trees lead to healthy harvests and communities!

Macronutrient Deficiency Symptoms

Nitrogen

Role of Nutrient: Nitrogen (N) affects the leafy growth of plants. Inadequate nitrogen can impair tree growth and productivity, but because ʻulu is a soft-wooded, fast-growing tree, excess nitrogen can make your ‘ulu grow quickly, diverting energy away from the fruit and requiring more frequent pruning to control.

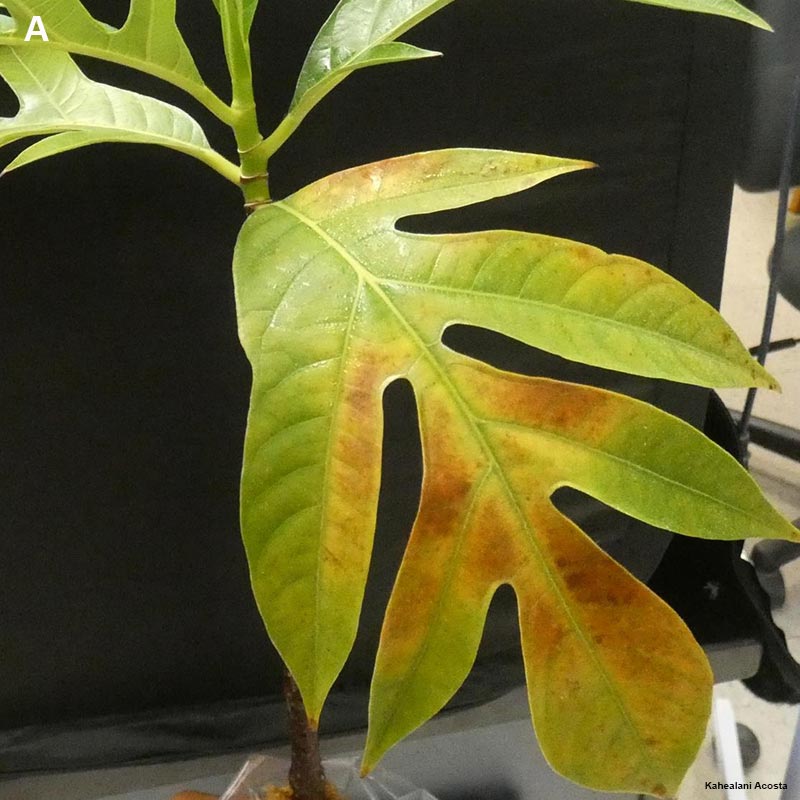

Diagnosis/Identification: The first symptom of nitrogen deficiency is the loss of leaf luster/shine. This is followed by the heavy yellowing of leaves, starting from the oldest leaves and progressing towards the youngest leaves occurring at the branch tip.

Common Misidentification: Many elemental deficiencies cause chlorosis, or yellowing of the leaves. However, other elements tend to either yellow around the veins or between the veins, or yellow from the tip or from the base, while nitrogen deficiencies will evenly yellow across the entire leaf.

Remedies: There are a few methods for treating nitrogen deficiency. One option is the application of a pure nitrogen fertilizer or nitrogen-rich amendments such as blood/bone meal, fish meal, bat guano, alfalfa meal, or heat-sterilized manure. Heat sterilization of manure is vital due to food safety concerns; to learn more about the sterilization requirements for manure, check out this USDA resource.

Another option for treating nitrogen deficiency is planting nitrogen-fixing plants nearby. For ʻulu trees, groundcover plants such as pigeon pea and perennial peanut are excellent nitrogen-fixing companions.

Aged organic compost + green mulch material can be added several times a year in order to balance nitrogen levels in the soil. This helps prevent leaching of nutrients and contributes to the health of the soil.

Animals such as chickens can also be incorporated into the orchard area to increase nitrogen cycling and availability; however, it is important to keep in mind the USDA regulations on manure fertilization as mentioned above if you have roaming animals and ground crops in the same area.

Considerations: Nitrogen is a highly soluble nutrient, meaning that it dissolves readily in water and can quickly be washed out of a soil system. Rainy areas should utilize more frequent small applications of fertilizers and amendments, while dry areas should be watered consistently during and between applications to avoid spikes in soil nutrient levels.

Demonstration of nitrogen deficiency in breadfruit showing the gradient of yellowing from the old to the young leaves.

Demonstration of nitrogen deficiency in breadfruit showing the loss of leaf luster/shininess as an early symptom.

Demonstration of nitrogen deficiency in breadfruit showing a whole leaf evenly yellowing.

Phosphorus

Role of Nutrient: Phosphorus (P) affects the metabolism and energy systems of the plant, and is used heavily in root growth and flower development. ʻUlu requires a relatively low amount of phosphorus, which is represented in our recommended N-P-K fertilizer ratio of 8-5-30.

Diagnosis/Identification: The symptoms of phosphorus deficiency are an unusually dark coloration to the leaves, followed by the development of dark brown splotches. Some leaf curling and contortion may also occur as phosphorus deficiencies can cause co-deficiencies in cations such as potassium.

Common Misidentifications: Phosphorus deficiency shares some traits with calcium deficiency; both can see the formation of brown spots and leaf curling/contortion. However, phosphorus deficiency manifests with less regular splotches of brown, and the leaf curling is less common than it is with calcium deficiency.

Remedies: Phosphorus deficiency can be treated through the application of natural amendments such as bone meal and fish meal, as well as a superphosphate fertilizer. Soluble phosphorus, such as phosphoric acid, can be applied foliarly in low concentrations.

Considerations: Overall, phosphorus deficiencies in ʻulu are unlikely if you are regularly applying fertilizers. Phosphorus is highly immobile in most soil types and is therefore less prone to leaching and runoff from heavy rainfall.

Demonstration of phosphorus deficiencies, including large brown splotches.

Demonstration of phosphorus deficiencies, including darker coloration of the leaves.

Demonstration of phosphorus deficiencies, including brown splotches that avoid in the interveinal areas.

Potassium

Potassium is for the transport and mobility of nutrients in the plant.

Role of Nutrient: Potassium (K) helps the transport and mobility of nutrients in the plant, and is vital for the development of the fruits. ʻUlu has a nutrient requirement profile similar to bananas, requiring a high amount of potassium to thrive. We suggest an N-P-K ratio of 8-5-30 to meet that high potassium requirement.

Diagnosis/Identification: In potassium-deficient plants, the older leaves pale and lighten, but don’t fully exhibit chlorosis (yellowing). The leaf tips may burn, and leaf margins may turn rusty. Necrosis (tissue blackening and death) may occur, starting at the outer edges of the leaves.

Common Misidentifications: Potassium deficiency shares some traits with magnesium and sulfur deficiency – as well as phosphorus deficiency in young trees.

In both potassium and sulfur deficiency, the leaves can lighten, the leaf tips can burn, and necrosis can occur. In potassium deficiency, however, necrosis is concentrated at the edges of the leaves, beginning at the base, while sulfur necrosis is concentrated along the stems. Sulfur deficiency is also strongly indicated by the yellowing of the stems, which does not occur with potassium deficiency.

In both potassium and magnesium deficiency, there may be some yellowing of the leaves and the burning of leaf tips. Potassium deficiency will not display full chlorosis, however, and the yellowing of the leaves wonʻt be concentrated between the veins of the leaves. Additionally, magnesium deficient ʻulu will maintain an area of green immediately around the veins of the leaves, and they might also develop small brown patches.

Remedies: Potassium deficiency can usually be prevented with a regular NPK fertilizer application 3-4 times per year. We recommend an 8-5-30 ratio of N-P-K; a conventional 10-5-20 or the organic Bioflora 6-6-5 + 8% Ca are both viable options as well.

Amendments such as seaweed, gypsum, and sulfate of potash are excellent options for providing a boost of potassium and improving uptake. Acidic soils can limit the ʻuluʻs uptake of potassium; if your soil is acidic, consider applying lime to reduce soil acidity and improve potassium uptake.

Considerations: Be careful to avoid overfertilization with Calcium, Manganese, and Sodium; these can reduce uptake of Potassium. Be sure to consider your soil pH before deciding on a treatment approach. Remember that potassium is highly water soluble; in rainy areas, it is especially important that you feed your trees regularly to compensate.

Demonstration of potassium deficiencies including yellowing and splotching of leaves.

Demonstration of potassium deficiencies including burning of the leaf tips and brown splotching beginning at the leaf tips/edges.

Demonstration of potassium deficiencies including rusty leaf margins and dark splotching. Although mold is likely attributed to the presence of mealy bug, this mold originated on the trees due to a K deficiency.

Calcium

Role of Nutrient: Calcium (Ca) is vital for the development and growth of plant cells, providing structural support to leaves and fruits. ʻUlu has a high demand for calcium, which is important for the development and quality of the fruits.

Diagnosis/Identification: In calcium-deficient plants, young leaves may contort and curl before they fully develop. It is possible that the weakened, calcium-deficient leaves are more prone to pest invasion, which may cause the leaf contortion associated with calcium deficiency. Irregular yellowish-brown spots may develop on the leaves, and flower production may diminish as well.

Common Misidentifications: Calcium deficiency shares some traits with boron deficiency; both deficiencies can have contorted and curled leaves and brownish-yellow lesions. However, boron-deficient leaves will thicken, becoming brittle and easily broken, unlike calcium-deficient leaves, which do not thicken or display brittleness.

Remedies: Calcium deficiency can be treated with a foliar (leaf) spray or soil drench using a natural product such as Water-Soluble Calcium (WCA); these products help to increase calcium absorption. Short-term treatments such as dolomite, lime, or calcium-heavy fertilizers can also improve calcium uptake. Bones, shells, corals, and other hard sources of calcium can provide a slow, long-term calcium source to your soils when mixed in as amendments.

Considerations: Calcium is highly water soluble. Maintaining consistent irrigation can minimize Calcium fluctuation levels; water plants consistently in dry areas, and add mulch layers in rainy areas to prevent excessive leaching.

Here, the lesions suggest a calcium deficiency.

Here, the leaf contortions suggest a calcium deficiency.

Here, the leaf contortions (left) and lesions (right) suggest a calcium deficiency.

Sulfur

Role of Nutrient: Sulfur (S) is essential for the synthesis of the proteins and amino acids that help plants grow. While it is not needed in the same quantities that nitrogen, potassium, phosphorus and calcium are, it is nevertheless vital to the growth of ʻulu.

Diagnosis/Identification: In sulfur-deficient plants, the early symptoms manifest after about six months of deficiency with spotting near the midrib and leaf veins. The leaf tipswill darken, burn, die off or hook prominently downward. After about one year of deficiency, the leaves lighten in color and turn brown along the midrib, and the veins can become a striking yellow color. Tissue death then occurs along/between the veins of the leaves.

Common Misidentifications: Sulfur deficiency shares some traits with potassium deficiency. With both deficiencies the leaves lighten, the leaf tips contort or burn, and necrosis can occur. In potassium deficiency, however, necrosis is concentrated at the edges of the leaves, while sulfur necrosis is concentrated along the stems. Sulfur deficiency is also strongly indicated by the yellowing of the stems, which does not occur with potassium deficiency.

Remedies: Sulfur deficiency can be treated with sulfur-containing amendments such as gypsum, sulfate of potash, or superphosphate; be sure to check the content of your fertilizers for sulfur content before applying.

Considerations: It can take a few months for applied sulfur to reach the leaves of the plant, so be sure to wait 2-3 months after treatment to assess the results.

Here we see yellowing veins and necrosis occurring along the veins and the early symptom of tip burn and hooking of the leaf tip.

This image displays yellowing veins and tissue browning/necrosis.

Magnesium

Role of Nutrient: Magnesium (Mg) is essential for the synthesis of the proteins and amino acids that help plants grow. While it is not needed in the same quantities that nitrogen, potassium, phosphorus and calcium are, it is nevertheless vital to the growth of ʻulu.

Diagnosis/Identification: In magnesium-deficient plants, the leaves display interveinal chlorosis (yellowing between the veins). Notably, however, the area immediately around veins remains green. The leaf tips may curl, and irregular brown patches may develop on the leaf tissue as well. Branch lodging (the bending over of stems) may also occur, especially in the Maʻafala cultivar.

Common Misidentifications: Sulfur deficiency shares some traits with potassium deficiency. In both potassium and magnesium deficiency, there may be some yellowing of the leaves and the burning of leaf tips. Potassium deficiency will not display full chlorosis, however, and the yellowing of the leaves wonʻt be concentrated between the veins of the leaves. Additionally, magnesium deficient ʻulu will maintain an area of green immediately around the veins of the leaves, and they might also develop small brown patches.

Remedies: Magnesium deficiency can be treated with aged organic compost to help maintain levels over the long-term. Foliar sprays or soil drenching with an amendment such as epsom salt or lime can be an effective and quick-acting solution to magnesium deficiency.

Here we see interveinal chlorosis with characteristic green surrounding the veins, suggesting a magnesium deficiency, this provides an example of leaf tip burn as well.

Interveinal chlorosis with characteristic green surrounding the veins, suggesting a magnesium deficiency.

Interveinal chlorosis with characteristic green surrounding the veins, along with leaf tip burn, suggesting a magnesium deficiency.

Here we see an example of stem/branch lodging suggesting a magnesium deficiency.

Micronutrient Deficiency Symptoms:

Boron

Role of Nutrient: Boron (B) is a critical micronutrient for the structure of plant cell walls and reproductive structures. While it is needed in smaller amounts than macronutrients, it plays an important role in ʻulu fruit development. An excess of boron can cause damage to the tree, however, so it is important not to over-apply.

Diagnosis/Identification: In boron-deficient plants, the stems and leaf tips often grow irregularly. New shoots often appear burnt, contorted or deformed, and necrotic brown spots can form between the veins. The most characteristic symptom of boron deficiency is the thickening, contorting, and embrittling of the leaves; boron-deficient ʻulu leaves will easily snap off when bent.

Common Misidentifications: Boron deficiency can be confused with calcium deficiency due to the similar structural roles that each nutrient plays. Both deficiencies can have contorted and curled leaves and brownish-yellow lesions; however, boron-deficient leaves will thicken, becoming brittle and easily broken, unlike calcium-deficient leaves, which do not thicken or display that same brittleness.

Remedies: Boron deficiency can be treated with granular or powdered Boron (such as Granubor) applied to the roots of the tree. Good irrigation is important, as the boron will dissolve and be taken up by the roots of the tree.

Considerations: Boron deficiency is most common in areas of high rainfall or drought, as well as in areas with rocky or sandy soils. ʻUlu growing in these areas may require more frequent applications of boron. Be careful not to over-apply, and allow for a minimum of 3 months between applications to prevent harm to the tree.

Here we see contorted and deformed leaves on an ‘Ulu, suggesting boron deficiency.

Here we see lesions between veins suggesting boron deficiency.

Here we see contorted and deformed leaves and lesions between veins on an ‘Ulu, suggesting boron deficiency.

Here we see contorted and deformed leaves and lesions between veins on an ‘Ulu, suggesting boron deficiency.

Iron

Role of Nutrient: Iron (Fe) plays a vital role in the production of chlorophyll and enzymes within the plant. While it is needed in smaller amounts than macronutrients, it still plays an important role in ʻulu growth.

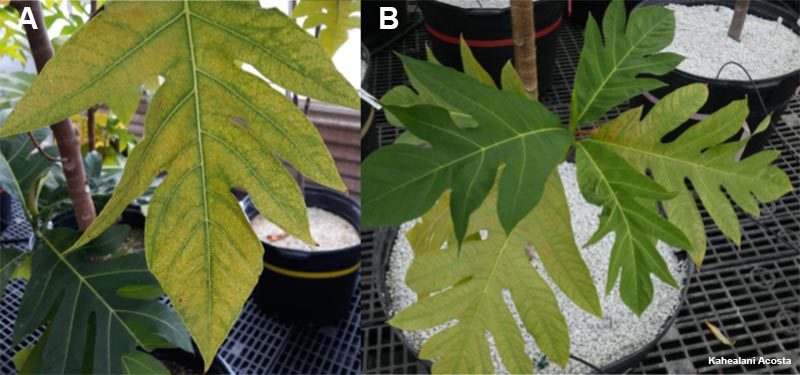

Diagnosis/Identification: In iron-deficient plants, the youngest leaves will develop interveinal chlorosis (yellowing between the veins), followed by the older leaves. The veins remain dark while the leaves yellow, and the growth and size of the leaves will both decrease over time.

Common Misidentifications: Iron deficiency can be confused with potassium and magnesium deficiencies.

Iron and Potassium deficiencies both exhibit yellowing of the leaves, but potassium deficiency only displays partial yellowing of the leaves and is accompanied by tip burning and tissue necrosis.

Iron and magnesium deficiencies both exhibit full yellowing of the leaves. However, magnesium deficiency is distinguished by the yellowing of the stem and an area of green immediately surrounding the stem; iron deficiency, however, is distinguished by green stems and yellow leaves.

Remedies: Iron deficiency can be treated in the long-term with dry or liquid iron compounds applied at the base of the tree and actively irrigated. In the short-term, foliar sprays of iron sulfate or iron chelate can provide immediate relief to deficient trees.

Considerations: Overwatering and excessive rainfall can contribute to iron deficiencies; if your trees are in a rainy area, keep an eye out for symptoms of iron deficiency and consider mulching the base of the tree to slow leaching.

Here we see the chlorosis between veins and the diminished leaf size (B) characteristic of iron deficiency. Note how the veins in have retained their coloration as the leaves themselves yellow.

Here we see the chlorosis between veins characteristic of iron deficiency. Note how the veins have retained their coloration as the leaves themselves yellow.

Want to learn more? Check out our Breadfruit Nutrient Management Guide.