Māmaki: Propagation and Management

If you’ve spent much time in Hawai’i you’ve probably heard of Māmaki, the Hawaiian herbal tea beloved for its rich earthy taste and its use in Lāʻau Lapaʻau (Traditional Hawaiian Medicine). Known scientifically as Pipturus albidus, this member of the nettle family is native only to pae ʻāina o Hawaiʻi (the Hawaiian Archipelago), and is generally found in the understory of tropical and subtropical wet forests at elevations between 200 and 6,000 feet. Māmaki is sometimes called the “nettleless Nettle” because it lacks the stinging hairs that characterize its relatives.

History

History

The Hawaiian people have many uses for māmaki, ranging from the creative and constructive to the medicinal. The hardwood can be used to make iʻe kuku, a type of club for beating kapa bark cloth, and the fibrous inner bark can be pounded into a type of kapa. The fruits can be consumed whole as a laxative or applied as a poultice, and tea made from the leaves is rich in antioxidants that may help regulate cardiovascular health and blood glucose levels. Studies have also found that māmaki leaf extract exhibits antimicrobial properties, furthering our understanding of its role in traditional medicine. According to the folks at Hawaii Forest Farms, there are at least 6 varieties of māmaki (P. albidus) under cultivation, primarily characterized by the color of the veins and the texture and color of the leaves. There is a lot of variation in the appearance and growth patterns of māmaki, and there are almost certainly more varietals out there that have eluded public view!

Why Māmaki?

These days, māmaki is primarily grown as an herbal tea. The taste is mellow and rounded with herbaceous and mossy notes, and it is enjoyed on its own or blended with other herbs and flowers like mint, lavender, and lemongrass. Māmaki also contains more potassium, calcium, and magnesium than other teas, according to one comparative analysis, and also contains various antioxidants and micronutrients. Public interest in māmaki as a tea has grown in recent years, thanks in large part to the popularization of bottled drinks from the likes of Shaka Tea Company and the availability of dried packaged teas in health food stores, often touting its medicinal properties.

If you’re a farmer or backyard gardener in Hawaiʻi, you may be wondering, “why should I grow māmaki?” While the market is still somewhat niche, the bulk dry organic leaf typically retails for $150-200 per pound. It is also a native Hawaiian plant, it thrives as a low-maintenance mid-story agroforestry crop, and it is the favored habitat for the rare endemic Kamehameha Butterfly to lay their eggs. (Co-plant it with Koa to allow the butterflies to complete their lifecycle!) So while you probably won’t make a business out of māmaki (unless you’re Hawaii Forest Farms or Ancient Valley Growers), it can be an excellent companion crop to include amongst your orchard or agroforestry plantings to fill space, provide some native habitat, and bring in some extra revenue on the side!

Propagating Māmaki from Seed

In October of 2022, Jonathan Hutchinson and Vi Girbino were commissioned to propagate ~300 māmaki plants from seed for the OK Farms Agroforest. The white, spongy māmaki fruits were collected from mature trees at OK Farms in Hilo and submerged in non-chlorinated water at room temperature, where they were allowed to soak and ferment for about 48 hours.

After soaking, the seeds are separated from the fruit by vigorous shaking, ideally with a “blender ball” or other wire mixing ball in a water bottle. The loose seeds were carefully poured off from the remaining fruit into a drained tray that was ¾ full of either pure Perlite or coconut coir. This was part of an experiment to determine which substrate works best for māmaki germination. The seeds were kept under an automatic mist watering system and allowed to germinate and develop for three months. Based on this experiment, māmaki seeded into perlite rooted deeper but had a lower germination rate, while the coconut coir sprouted prolifically but had shallow root systems. it seems likely that a 1:1 mix of perlite and coconut coir may provide optimal deep-rooted germination.

When the seedlings were at least 2-3 inches tall, they were carefully separated and their roots untangled before each seedling was planted into a 1:1:1 mix of re-hydrated coconut husk, black cinder, and pro-organic mix Hawaiian blend soil. These seedlings matured outside in pots for four months until they were at least 10-12 inches tall, watering when needed.

How & Where to Plant

How & Where to Plant

Māmaki will thrive in the partial shade at elevations between 200 and 6,000 feet in the tropics and subtropics of Hawai’i. They can grow to heights of 20+ feet, but should be trimmed as necessary to allow for harvest. They require decent soil drainage, so mixing in a bit of black cinder is recommended. At the OK Farms Agroforest, our māmaki has been thriving when planted 2-3 feet from our ‘ulu trees and interplanted with nearby roselle hibiscus, lemongrass, and basil. The roselle diverts the pest pressure, the lemongrass can be mulched to provide a pest-repellent ground cover, and the basil has the added benefit of drawing in pollinators. At the end of the day, you can combine each of these interplanting crops to make a delicious tea!

Materials and Equipment:

- 3″ shallow planting trays for propagation

- 4″ seedling pots

- Reusable water bottle or water-tight container for shaking

- Blender Ball or similar item to agitate fruits while shaking

- Coconut coir

- Perlite

- Black cinder

- Pro-organic mix Hawaiian blend soil (or similar)

- Fresh Māmaki Fruit

- Misting hose/irrigation system for watering plants

- Non-chlorinated water

Propagation Step-by-Step:

- Harvest fresh, white māmaki fruits from mature, healthy plants that share environmental conditions (elevation, temperature, rainfall) with the area that you intend to plant

- Soak the fruits in non-chlorinated water for 48 hours at room temperature

- Vigorously shake the māmaki fruits in water (preferably with a metal “blender ball” to break up fruits from seeds) until the seeds have visibly separated from the fruits

- Carefully pour the seeds and water into your potting medium (1:1 mix of perlite and hydrated coconut coir) without pouring fruit into the potting medium

- Keep the potting medium damp with daily misting for 3 months

- When seedlings reach 2-3 inches in height, transfer into 4″ pots with 1:1:1 mix of re-hydrated coconut husk, black cinder, and pro-organic mix Hawaiian blend soil

- Allow to grow in partial sun until seedlings are 12″ tall, watering as necessary to keep the soil lightly damp but not wet

- Outplant seedlings when they’ve reached 12″ tall into the understory of established trees

OK Farms Agroforest: A Learning Experience

OK Farms Agroforest: A Learning Experience

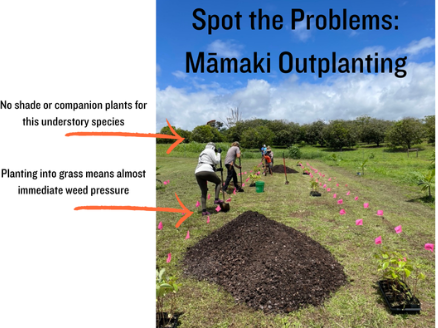

At the end of May 2023, the OK Farms Agroforest held a community outplanting event for the young mamaki, planting ~350 seedlings in ~3 hours. This outplanting would prove to be ill-fated, however, because of a few key missteps. First and foremost, mamaki is an understory crop, and it requires partial shade in order to thrive. By planting the seedlings into an open area, they were left vulnerable to pests and overexposure to sunlight, and suffered low growth and high mortality as a result.

Another vital mistake was planting the māmaki directly into the unprepared ground, without any tilling or spading, mulching, or weed mat to help hold back the weeds. Consequentially, the māmaki was almost immediately at odds with highly competitive weeds, which quickly anchored themselves in and around the macadamia nut mulch that we had put around the seedlings.

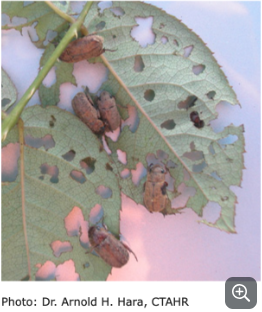

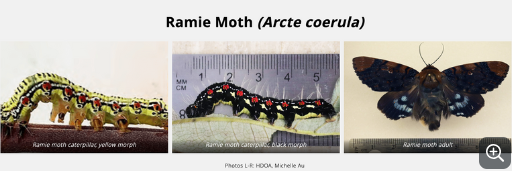

After a month or so had passed, the pest pressure affecting the māmaki became evident. Ramie Moths (Arcte coerula) and the Chinese Rose Beetle (Adoretus sinicus) were found defoliating the young māmaki, and the māmaki rows required biweekly weeding to keep the weeds down.

In June and July of 2023, beds of cardboard and mulch were added around the māmaki to reduce the pest pressure. The soil was treated with an aerated compost tea to boost available nutrients and kickstart the soil food web, which helped increase mycelium and arthropod activity in the soil. Additionally, dim solar lamps were added to to reduce the pest pressure facing the māmaki by attracting the rose beetles away from the plants. These introductions helped, but without companion crops to provide shade, the māmaki population continued to dwindle. In July of 2023, additional crops were added to the rows: ice cream bean, gliricidia, moringa, pigeon pea, and the edible roselle hibiscus.

The roselle, as it happened, would prove to be the greatest discovery in this experiment: Chinese Rose Beetles love hibiscus, and planting them near māmaki will draw the pest pressure away from the more sensitive native plant without dramatically impacting the roselle crop.

Eventually, after losing ~320 of the 350 outplanted mamaki seedlings, the team decided to cut their losses and transplant the surviving mamaki to a more suitable environment. Māmaki do not transplant well, but when provided the proper companion planting, pest diversion, and weed suppression, the survivors finally began to thrive.

Common Pests

As mentioned before, the Ramie Moths and Chinese Rose Beetles are two of the biggest pest threats for māmaki.

Ramie Moths are a high-impact invasive species that primarily impacts māmaki, outcompeting the Kamehameha Butterfly for habitat in the process. So far they’ve been detected on Maui and the Puna and Hilo districts of Hawai’i Island. If you think you’ve found a Ramie moth, photograph it, capture it if you can, and send the photo/sample to the Big Island Invasive Species Committee (BIISC) for identification and control assistance!

Chinese Rose Beetles are a more common and less māmaki-specific pest in Hawai’i, but they can be controlled with the use of easily built traps or diverted away from sensitive crops through the use of companion plants like hibiscus. These beetles live in the leaf-litter and mulch around the base of plants, coming out to feed around dusk for a few hours before returning to their protected homes. Their presence can be detected by the presence of the buckshot-like holes affecting the leaves of the plants, or visually with a flashlight if you are out after dusk.