Breadfruit Production Across the Pacific:

Contemporary Agroforestry Practices in Tonga

Text and Photos by Dana Shapiro

INTRODUCTION

In February 2023, Pacific Island Farmers Organisation Network (PIFON) members Nishi Trading (Nishi) and Hawaiʻi ʻUlu Cooperative had the opportunity to participate in a knowledge exchange in Tongatapu, Tonga. The two organizations have similar processing operations and product lines; they also experience many of the same challenges related to building the breadfruit value chain in their respective areas.

In addition, Nishi and the ‘Ulu Co-op share similar values, mission and vision around breadfruit industry development — with the overarching goal of increasing local food security and community wellbeing through capacity building of small-scale, diversified farmers. The information recorded within this blog was shared by local agricultural practitioners in Tonga.

OVERVIEW OF TONGAN AGRICULTURE

Most commercial agriculture in Tonga focuses on field crops, not tree crops. Primary staple crops include yam, taro, sweet potato, and cassava. One local variety of cassava, or manioke in Tongan, is harvestable after just three months. The most popular sweet potato variety is called “Hawaii” and has white skin and purple flesh, though is not the similar colored Okinawan sweet potato variety popular in Hawai‘i.

Most Tongan farms are 8 acres in size, which is the traditional tax allotment provided to households by the government. For this reason, efforts to promote incorporation of breadfruit into commercial agricultural systems are currently focused either allocating 1-2 acres out of the typical 8-acre farm, or integrating trees along the perimeter of the farm and as rows installed around other cropping areas, such as to demarcate between beds of varying field crops.

Historically, copra (dried coconut meat from which oil is obtained) was an important export industry in Tonga from the early 20th century through the 1990s, at which time coconut fields began to be bulldozed for pumpkin production — another export-oriented market that crashed in the early 2000s due to both production and logistical challenges. Pumpkin varieties such as kabocha are still a big export crop, though not as dominant as they were a few decades ago. Coconut trees still dominate the landscape, and old copra orchards – while not as maintained as they used to be – continue to be harvested for local and export markets.

A large proportion of the Tongan population works in agriculture. According to local practitioners at an agricultural development nonprofit called Mordi, some 70% of Tongans are employed in agriculture, with only about 2.5% commercial farmers, 50% semi-commercial (meaning they have some off-farm income) and the rest (47.5%) subsistence farmers.

System Design

Traditional Tongan breadfruit production systems primarily harvest from wild grown trees in the bush, with some households planting trees in the backyard garden. Most homes have between 1-5 trees, though some have none. At the village level, small villages tend to have the equivalent of about 1 acre of breadfruit collectively (50-60 trees), and larger villages might have 2-3 acres worth of production.

A baseline study of 6 villages conducted by Mordi found that around 40% of fruit produced in home garden settings was consumed by the family, compared to only about 30% of fruit produced in the bush. Around 30% and 25% of fruit was shared or gifted to neighbors in each setting, respectively, and about 30% of the fruit in home gardens went to waste compared to about 40% in the bush. A much smaller percentage of fruit in both settings was sold commercially (only 5-10%). The Tongan Ministry of Agriculture has expressed interest in conducting a larger baseline study on breadfruit production across the country in the near future.

Common Breadfruit Varieties in Tonga

According to Mordi, the top four varieties in Tonga include meifisi (pictured above – “‘Ulu Fiti” in Hawaiʻi), mafala (“maʻafala”), maopo, and kea – all seedless or mostly seedless varieties. Another four varieties are prevalent but less desirable for commercial use.

In the photo above, farmer Felipe points to a maopo variety tree, indentified by the full glossy leaves with little to no lobing.

Photo above: breadfruit in Tonga – maʻafala (left), meifisi (right).

Photo above: breadfruit in Tonga – kea (left), aveleloa (right). Aveloloa has a distinctly “long” shape and is a preferred variety for Faikakai Tōpai (a tongan dessert made with dumplings covered in a sweet coconut syrup) and roasting because of its soft texture.

Preferred varieties for processing and eating are the large, seedless varieties, such as kea and loutoko (pictured above). However, the maʻafala variety, which is smaller, is considered to have good fruit quality and taste and is also desirable.

Integration of Agroforestry Principles

More recently, commercial or semi-commercial breadfruit production systems have been promoted as either orchard blocks or perimeter plantings. Alley-cropping is a common traditional practice in Tonga, usually with coconut trees planted in rows and field crops such as yam, taro, cassava or sweet potato planted in the alleys. Banana and even giant taro are also sometimes used as the taller row crop.

Two 1-acre orchards were planted in Tonga about 5-6 years ago by Nishi Trading and a farmer named Felipe. Nishiʻs orchard was planted in 2017 with 62 trees at a spacing of about 26.5 ft x 26.5 ft. Sparse other tree crops are planted among the breadfruit trees including banana, sandalwood (a tropical hardwood being promoted as a long-term investment crop for small farmers), and coffee.

Field crops were alley cropped in this orchard when the trees were younger but have been largely phased out. Remnant turmeric and pineapple were the only alley crops left in a few of the alleys, shown in the photo below.

The trees in Nishi’s demonstration orchard started fruiting at 3 years old. The seedlings were propagated via root suckers, with 4 different varieties. The trees have been pruned heavily, with first topping at 2 meters (6.5 ft) and thinning to optimize air flow. This saved the trees during cyclones, when larger trees could have been badly damaged. Now the trees are maintained at about 2.5 meters with annual pruning (reduced to about 8 ft each year).

Alley Cropping

Nishi was happy with the success of the initial 1-acre trial orchard and has since planted another several hundred trees on a nearly 7.6 acre parcel that are now about 1 year old, the photo below shows pineapple intercropping. This field is currently being prepped for expanded interplanting with taro. Spacing on the new field is wider than the first demo acre to allow for a tractor and trailer to drive between the rows during harvesting. No fertilizers or pesticides have ever been applied to either of the Nishi’s breadfruit orchards to date.

Felipeʻs orchard has wider spacing than Nishi’s 1-acre demo at about 29 x 29 ft with 52 trees per acre and is still intercropped actively. The photo below shows breadfruit alley cropping with giant taro and banana.

Mordi has distributed thousands of breadfruit trees for free over the past few years, and one of the farmers who planted about 40 of these trees (a relatively large amount) does not harvest his fruit currently and instead lets friends and family access what they want. His farm was relatively unmaintained overall but incorporated a unique blend of the traditional alley cropping system with rows of coconut trees intermixed with few rows of breadfruit, and alternating alleys of taro and cassava.

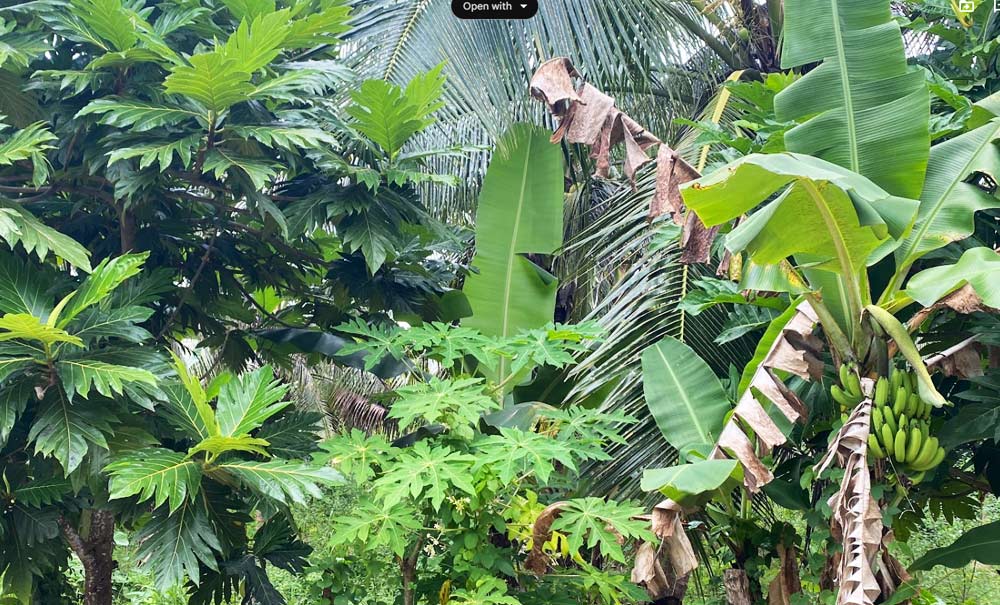

Commonly intercropped species in Tonga include breadfruit, papaya, coconut and banana. These crops are also commonly grown together in Hawaiʻi.

Cover Cropping with Mucuna

In Mordi’s demonstration fields at its headquarters, mucuna is used as a cover crop to prep beds, including alleys between trees, for future field crops such as taro. Mucuna is a legume that is thought to help restore the soil. It dies down on its own after about 6 months, at which time other crops can be installed. Mucuna is also used as a companion crop planted within rows of trees in Nishi’s trial orchard – a project funded by the Australian government to trial commercial citrus production in Tonga.

Perimeter Planting

The second style of production being promoted in Tonga is perimeter planting, where breadfruit trees are established along the property boundaries. The photo below shows such a planting at a local school, where breadfruit and coconut were planted together along the fenceline.

The photo below shows a perimeter planting demonstration at Mordi where breadfruit trees are used as a separation between different parts of the farm and education site, in this case separating the greenhouses from the fields.

The photo below shows a perimeter planting demonstration at Mordi where breadfruit trees are used as a separation between different parts of the farm and education site, in this case separating the greenhouses from the fields.

Harvest and PostHarvest Practices

In Tonga it is a traditional practice to complete a postharvest water soak. The tools used for harvesting are also similar to those created by Tokyo University for Nishi and Uncle Stanley in Hawaiʻi.

Propagation

A traditional method of transplanting in Tonga is uprooting very large root suckers and transplanting them directly into the ground. In the photo below, Mordi’s greenhouse is full of root sucker propagated trees, one of two preferred methods alongside air layering. Trees commonly start fruiting 2-3 years after planting in Tonga, with no fertilization.

Conclusion

ʻUlu (breadfruit) is one of the major staple foods within the Pacific Islands and one that has the potential to transform tropical agriculture and solve some of our major food security issues. By collaborating on research and sharing best practices, Tonga and Hawai‘i organizations have the chance to learn from each other and continue the development of new and improved breadfruit production and processing methods.

Shared challenges that both regions currently face include the economic viability of commercial or semi-commercial ‘ulu production, labor shortages, high cost of production in both farming and processing systems, consumer awareness, demand and willingness to pay for value-added breadfruit products. Land tenure is also an issue, as most farmland in both locations is leased rather than owned, and lease terms are typically not designed for tree cropping.

Meanwhile, some of the opportunities common to both Hawai‘i and Tonga include the environmental adaptability of breadfruit in a changing climate as well as a growing consumer demand for healthy staple foods that are both local and gluten free. Institutional support is also growing for agroforestry; in Tonga there is increased NGO and government support programs while Hawai‘i has recently gained access to more USDA resources, including farmer financial incentive payments. With greater collaboration, such as the learning exchange documented here, breadfruit farmer organizations in Tonga and Hawai‘i look forward to creating a more efficient, sustainable, and profitable breadfruit industry for their communities and the Pacific region.